There’s a new group on Facebook, Caid Dyers, that I am really excited about. We have some wonderful fiber artists in the area and it is so much fun to get together and share ideas! I recalled, recently, how much fun I had working on a Pentathlon entry in 2009, so I decided this was a good place to share what I learned.

Many thanks to Bjo Trimble and Griffin Dyeworks, for providing materials, instruction and, most of all, inspiration!

<><><>

These woolen hanks are handspun and dyed to represent some of the possible colors that were obtainable to dyers in medieval Scotland. I specifically chose the wool to spin from sheep that are descendents from the area during this period and selected only a few of the natural dyestuffs available to local dyers. I very much wanted the look and feel of my fibers to be something familiar to my own SCA Scottish persona.

Trying to create a Scottish persona in the SCA is not an easy task. Little evidence, if any, is left to indicate what clothing was worn in medieval Scotland. Most textiles that have been discovered through excavation have been found only in burial sites. These have, consequently, been fragmented and difficult to date, and the dyes have been lost through leaching and soil contamination. The following poem, written originally in Gaelic, and translated by Alexander Carmichael in 1928, reflects the fate of much of the clothing produced and worn in rural Scotland during this time:

This is no second hand cloth,

And it is not begged,

It is not the property of cleric,

It is not property of priest,

And it is not property of pilgrim;

But thine own property,

O son of my body,

By moon and by sun,

In the presence of God,

And keep thou it!

Mayest thou enjoy it,

Mayest thou wear it,

Mayest thou finish it,

Until thou find it

In shreds,

In strips,

In rags,

In tatters!

There is quite a bit of evidence, however, of the importance of wool in local animal husbandry. Bones found at numerous castle sites have been predominantly sheep bones, with very small numbers being from sheep under two years old. Evidence indicates that most sheep were kept to a mature age, thus indicating that sheep were kept for wool production rather than meat. Several 14th and 15th century Coldingham Priory records indicated that they kept a flock of over 2000 sheep, while Melrose Abbey had in excess of 12,000 sheep in its flocks.

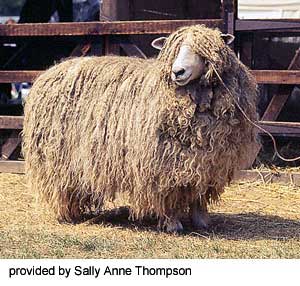

There were two principal types of sheep in medieval Britain, a small sheep producing short wool and a larger sheep producing long wool. The long-wooled sheep was found in rich grasslands, marshes and fens and produced wool, prepared by combing, and used for lighter worsteds and serges (materials which were not usually fulled).

I used the combed long-wool of the Lincoln (one of three breeds that accounted for the most wool production during the Middle Ages), whose fleece is carried in heavy hair-like locks. The staple length is very long. Lincolns produce the heaviest and coarsest fleeces of the long-wooled sheep.

I also used Swaledale tops, from a horned breed originating in medieval Yorkshire,

White Cheviot, originating on the border of Northumberland and Scotland, and long recognized for its durability and ability to hold and reflect dye coloring well, and Blue faced Leicester, which originated in Northumberland.

Sheep with long, lustrous wool have been in Leicestershire, England since the earliest recorded history of the British Isles and are responsible for the improvement and development of other long-wool breeds. They are closely related to the Border Leicester sheep found in Scotland.

I also used Merino wool top, which was an important import from Spain to the British Isles during the late 14th and 15th centuries. Long periods of war in Britain, as well as taxation problems, affected the local wool supply during this period; thus Spanish Merino was commonly used for textile production. I love the feel of this wool, and it is a joy to spin!

<><><>

After spinning, plying and setting the twist in the yarn, much of the yarn had to be further prepared for dyeing by adding mordant to the fiber. Mordants are mineral salts that become absorbed by the fiber and permanently link to its molecular structure. They guard against light and moisture, thus improving light-and wash-fastness, prevent color bleeding, and brighten or change some dye colors. Medieval dyers commonly used alum, copper and iron compounds as mordants. Salt and cream of tartar were often also used as dye additives, to set or brighten color, or to add softness. I also used club moss, a lichen, as both a mordant alternative to alum and a substantive dye. Also called oak moss, it is very common in many parts of Scotland.

After the necessary mordants were applied to the yarn, I was ready to begin the dying process. While we are unsure of the Scottish style of dress, there is ample evidence that both the Irish and the Scots, who share a common ancestry, were fond of bright colors. In the 1150 manuscript, the ‘Tain Bo Cualnge’, there are recorded color names for green, dark gray, purple, streaked gray, black, red, dull gray, reddish gray, red brown, blue purple, pied yellow and dun.

Scottish dyers had the use of a wide range of native dye plants, but we also have written records of imported dyestuffs to Scotland during the 15th and 16th centuries. One ledger book from the ten year period between 1492-1503 lists madder, woad and alum being sent to Scotland from the Netherlands. A more comprehensive list is available from 1612, which includes quite an extensive selection, including:

-

- Allome (alum)

- Anneill of barbarie (indigo)

- Ashes, pot ashes (potash) woad or soap ashes

- Brasill (brazilwood)

- Cochanneil (cochineal)

- Galles

- Frenche granes or Ginny (probably Persian berries)

- Grane of Civile in berries (cochineal)

- Grane of Portugal or Rota (cochineal)

- Indicoe of Turkie & the West Indies (indigo)

- Lyme for litsters

- Lit callit orchard lit (purple lichen dye)

- Litmus for litsters (prepared purple lichen dye)

- Mader

- Shoomak (sumach)

- Woad, Iland grene woad

- Stra woad

- English woad

- Woadnettis

- Fustick or blew brissell

- Brissile of Fernando Buckwode (Pernambuco wood)

<><><>

For my project, I used six dyes, based on availability:

weld – soak dried, chopped weld in warm water, with a pinch of washing soda

madder – ground madder in warm water, with small amount of cream of tartar

cochineal – ground bugs added to distilled water

safflower – dried petals soaked in a vinegar water solution; remove petals and add water; color brightened with soda ash solution

cutch – strained dye liqueur added to dyepot with wet, mordanted fiber; color deepened with re-dying in new cutch

woad – a complicated procedure involved making a woad solution in advance and extra precautions to ensure excess oxygen does not enter the (unmordanted) fibers

<><><>

With combinations made using these six dyes and three mordants, I was able to get quite a nice variety of colors. Whatever the clothing of the medieval Scotsman, his garments were colorful!